I’d read lots of blogs before coming to Spain, so overall I knew what my teaching job would entail. The biggest surprise, however, was the classroom organization of the Spanish high school. A couple days before starting, my boss gave me my schedule and told me what hours I’d be with what age groups. But my main question was, how would I know which room they were in at what times, if my schedule and theirs were always changing?

Turns out, the education system is set up here so that students stay with one group of classmates in one room the whole year (apart from a few select classes—there is a music room, for example, since they need a place to keep drums and keyboards.) Teachers rotate in and out of the classes, and students stay put. It’s completely different from what I’m used to, and after partaking in it all year long, and asking several European friends and my own students about their experiences, here’s my opinion on the matter:

Pros:

Lighter Load

Students don’t need to carry around heavy textbooks on their backs, or God forbid, resort to rolling backpacks. In the U.S., there is much debate and concern about the damage to students’ bodies from carrying around textbooks, notebooks, pen cases, after-school sports material, etc. Of course, students normally have lockers, but this isn’t a cure-all. Realistically there is not always time between classes to go to your locker, and I had a lot of friends in high school who never used their lockers at all. Plus, yours may be so cluttered with Justin Bieber paraphernalia and magnetic pencil holders and mirrors that there’s really no room for the non-essentials like textbooks anyway. (Side-note, Spanish students are OBSESSED with the idea of American lockers, thanks to the movies.)

Class Cohesion

Some of my Italian and French friends, who had a system of classroom arrangement similar to that of a Spanish high school, say they see the benefit in staying with the same group of classmates for the whole year. To me, it seems a social handicap as it would be difficult to break beyond that small circle of friends, but they say it provided security, as you got comfortable with your classmates and were thus more likely to participate and speak up in class. My students here also commented that, overall, they like this feeling of closeness.

Cons:

Honestly, I see more cons in the situation. I recognize that I grew up with the U.S. system, so maybe I’m biased, but I truly feel that in high school (we’re NOT talking about primary school here), it’s beneficial for the students to change classrooms. Here’s why:

Class Materials

In high school, you have demanding, specialized subjects. At least in the U.S., you also have Advanced Placement (A.P.) courses that are designed to be college-level. In Chemistry, we had lab tables for experiments, cabinets to store lab-coats and goggles; emergency eye-washing machines on two sides of the room. But we even had the most basic things—a periodic table of elements hanging on the wall! In my high school in Spain, there is no supporting material anywhere on the walls, since each classroom serves as a place for English, science, math, Spanish, Euskera, geography, and history. (There is a designated lab room, with beakers, microscopes, and other materials, but a Biology colleague told me that many science teachers opt to stay in the classroom and teach out of the book.)

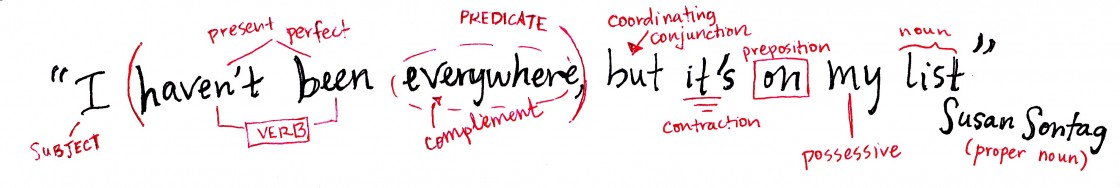

As a language teacher, this point is crucial. In my Spanish classes in high school, the walls were covered with posters to remember the question words (who/what/where/why/when/how/how much), verb endings and conjugations, idiomatic expressions, etc. If we struggled to remember something, the teacher could walk over to a poster and point to “Qué” instead of “Quién.” Items in the class could be labeled, so basics like “clock,” “whiteboard,” “desks,” “wall,” and “door” were engrained in our mind from the get-go. There was a calendar the teacher would change daily, so we learned days and months with little effort. This DOES NOT HAPPEN in classrooms in Spanish high schools, and I get so discouraged when a 2nd-year student can’t even remember how to say “how.”

It’s easy to see why, logistically. My school has 16 groups of students, so this would mean investing in 16 sets of verb posters, 16 periodic tables of elements, 16 mathematical posters for geometry classes. It’s not always economically feasible. Plus, fitting posters and material for six different subjects onto three classroom walls—subtracting the side with the windows—would be difficult and possibly distracting. Students would be staring off at the symbol for Iron while I’m trying to hammer home the difference between “who” and “what.”

The main room at the private English academy where I work. Granted, it’s for younger kids, but the walls are expertly decorated.

Teachers’ Organization

As teachers, we have a Sala de Profesores where we each have a little mailbox and a cabinet to keep material. Teachers generally bring a pencil pouch (even lugging their own whiteboard pens and chalk around, because students can’t be trusted in the classrooms not to throw the chalk while the teachers are switching rooms!) and the textbook to class. In my high school classes in California, teachers all had an entire section of the room for their own desk, book shelf brimming with binders and material, and their own computer (and maybe printer). I grew up in a nice area, but the school was public—nothing fancy. I feel like having a classroom as a home base helps the teacher to be organized. It is much simpler for a teacher here to just bring a textbook to class, and therefore rely more on textbook learning, than to shlep art supplies, supplemental material, binders full of printouts, boardgames like Taboo, or English storybooks to help stimulate English learning and conversation. Sometimes I arrive to class and realize the material I need is actually still below in my sad little cabinet, or that I have the 2nd-year book but forgot to bring up the 3rd-year book for next period’s class.

Student Energy

Passing periods for students are five minutes where they can stretch their legs, grab a snack, some water, or chat with friends. You could argue that students then re-enter each new class hyped up and are hard to calm down again, but on the flipside, the chance to move around a bit between classes can help to refocus them and prepare them for the next hour of class. In my school it’s technically against the rules for the students to go out into the hallway while the teachers are switching rooms (though of course, they do it anyway).

Limited Social Mobility

In high school, I enjoyed seeing certain friends in science, others in English, and a different group in math. It’s a chance to meet a broad spectrum of people. Also, that kid I absolutely hated in fourth period? At least I only had physics with him. And the disruptive one who made the minutes feel like hours wouldn’t dare try out an A.P. class, so at least I was safe in American History. In Spain, if you’re with your arch-enemy, you’re with him for good—possibly for all six years of secondary school.

Static Learning Environment

For the most part, the students aren’t just together for the one year; they start with their group in the first year of high school, and finish with them in year four, minus a few changes and occasional merges of groups. (4 groups of 2nd-years turns into 3 groups of 3rd years, for example, since some students are held back.) They may also continue together if the student chooses to advance to bachillerato, the optional final two years of high school. This means that if you randomly got stuck in a slower or rowdier group in your first year, you’re basically screwed. I have three classes of third-years; one is average, one is notably rowdy due to lots of boisterous boys; and one is a group of absolute angels, who have the highest English level of any of my students in the whole school. Why? Because they’ve been together since their first year, and three years of good behavior means approximately one extra year of English practice, as the professor probably loses a third of the class period just yelling at students to be quiet, dealing with the disruptive kids, or filling out discipline forms before sending the student to detention. So it’s really the luck of the draw—the kids that by chance got placed in the calm class have a really positive learning environment and can excel easily, and the kids that by chance got placed in another class lose a lot of the teaching time to behavioral issues. In my nightmare classes, I always have a couple of really motivated students who seem so defeated when the problem children won’t pipe down—they’ve been dealing with this same story for several years, and can’t get what they want out of the class because it’s so stop-and-go. Such a shame.

So what’s the solution? I’ve commented before that language teaching could use a major overhaul in Spain, but the U.S.’s method is equally if not more abysmal, so I’m sure it doesn’t all have to do with classroom arrangement. Both techniques have their advantages and disadvantages, but I am certainly partial to the American high school.

I should mention that not every high school in Spain does things the same way; others are more similar to the American method (even complete with lockers, *gasp!). Also, my high school in Bilbao has under 300 students, so I’m sure relative size has a lot to do with different arrangements.

Which arrangement would you prefer? Can you see any more pros or cons that I left out?

Pingback: dan anton army()

Pingback: dan anton army()